Wednesday, December 23, 2020

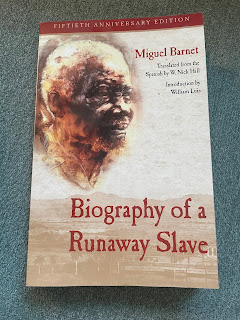

Cuba - Biography of a Runaway Slave

Sunday, November 22, 2020

Croatia - The Ministry of Pain

Book 39: The Ministry of Pain - Dubravka Ugrešić

____

The book takes place almost entirely in Amsterdam, but the former Yugoslavia, and the war that tore it apart, is always present. Tanja Lucić is a professor of Slavic literature...and a refugee. Most of her students are also refugees, and she struggles to figure out how to read the material of their home country without causing further harm. She takes on the role of psychiatrist - while battling her own demons.

What results is an in-depth look at how people adapt to life in a new country (or how they don't). Each character brings their own experiences of the war and subsequent fight to rebuild their lives.

Friday, October 23, 2020

Côte d'Ivoire - Love-across-a-Hundred-Lives

Book 38: Love-across-a-Hundred-Lives - Werewere Liking

Friday, September 25, 2020

Costa Rica - Unica Looking at the Sea

Book 37: Única Looking at the Sea - Fernando Contreras Castro

"Inside the great landfill at Rio Azul, Única and her friends, her family, society's cast-offs, struggle to survive on what those in the city throw away."

Tuesday, September 1, 2020

Republic of the Congo - Johnny Mad Dog

Book 36: Johnny Mad Dog - Emmanuel Dongala

"Johnny Mad Dog, age 16, is a member of a rebel faction bent on seizing control of war-torn Congo. Laokolé, at the same age, simply wants to finish high school. Together, they narrate a crossing of paths that has explosive results. Set amid the chaos of West Africa's civil wars...Emmanuel Dongala's powerful, exuberant, and terrifying new work is a coming-of-age story like no other."

This book took me a while to get into because I wasn't really in a great headspace for a war novel. And this is. But it's a well-written war novel. It's hard. It's disturbing. But hang in there for Laokolé. She'll make the read worth your time...

Friday, August 7, 2020

Colombia - One Hundred Years of Solitude

Sunday, May 24, 2020

China - The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices

Book 34: The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices - Xinran

Tuesday, May 12, 2020

Chile - The House of the Spirits

Book 33: The House of the Spirits - Isabel Allende

Sunday, April 5, 2020

Chad - Told by Starlight in Chad

Book 32: Told by Starlight in Chad - Joseph Brahim Seid

This book is a small collection of folklore that has been written down, passed on from the oral tradition. Each story is recognizable as the Chadian version of stories found in basically every culture. An interesting, though short read.